Operation Mushtarak

All together now

A military offensive against the Taliban in Afghanistan shows some early success

Feb 16th 2010 | KABUL | From The Economist online

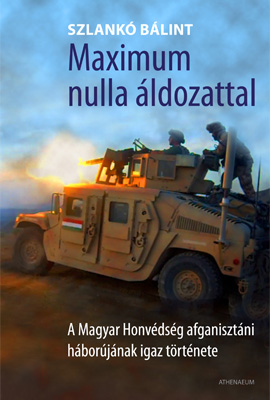

OPERATION Mushtarak, which was launched on Saturday February 13th as a joint effort between Afghan and NATO forces, has so far proven to be a moderately successful affair. The goal was to clear Marja, a big opium-producing town and the main Taliban stronghold in the southern province of Helmand. The territory was well suited to defenders, who could have taken advantage of an intricate web of irrigation ditches, small alleys winding between mudbrick houses and mounds of earth between the canals. One American commander described it as the worst terrain on earth, ideal for slowing down the advance of even the most powerful army. Yet the fighting has, reportedly, been limited.

The biggest allied offensive in Afghanistan since 2001 is a part of the recent Western push to turn the war against the Taliban. Operation Mushtarak—“Together” in Dari Persian—makes use of some 15,000 allied troops, roughly half of them Afghans, most of the rest American Marines and British soldiers. By Tuesday the offensive had succeeded in putting NATO and Afghan forces in control of most of the target area, according to coalition officials. But occasional fighting continues between militants and coalition troops who are moving from house to house. The danger of explosives is particularly severe. Clearing the town entirely could take weeks.

It is problematic that civilians have suffered in an operation that is, in part, designed to win support from local people. So far at least 15 non-combatants have been killed, 12 of them when a coalition rocket missed its target (although Afghan officials say three of the victims may have been militants). At least four NATO soldiers have died, three in a bomb explosion and one in a gun battle. And at least 30 insurgents have died. More than a 1,000 Marjan families have streamed into Lashkar Gah, the provincial capital, refugees from the well-advertised operation. The government says it is looking after them, though a local human-rights group says supplies have not been forthcoming. Amir Mohammad, a Marja refugee interviewed in Kabul, said the Taliban had tried to stop people leaving.

Marine commanders say that the insurgents have shown less resistance than had been anticipated. Many are believed to have fled in advance of the invasion, although American forces have come under fire from snipers and there have been reports of day-long gun battles and attempted suicide attacks. As expected, the biggest obstacle is hidden explosives: roads are mined, houses are booby-trapped. The roads into Marja, especially, are dangerous. British forces, given the task of taking Nad Ali, a town north-east of Marja, have been quicker to reach their target.

Marja, a town of nearly a 100,000 people, had previously been cleared in May when a four-day operation killed dozens of militants and saw narcotics seized. But NATO forces withdrew after the battle and the Taliban slipped back. By the end of last year American commanders estimated that Marja was home to as many as 1,000 enemy fighters and served as the insurgents' capital.

This time the coalition claims that it intends to stay. Under a new doctrine of “clear, hold, and build” it plans to patrol the roads of the area, build new schools and clinics, establish decent local government and create jobs. But convincing locals that this will really happen will not be easy. Many of them support the Taliban, if only out of fear and an expectation that, in the long run, the insurgents will be back. NATO forces are for now disinclined to destroy the poppy crop, which provides a livelihood for many residents.

Nonetheless, many locals will be happy to be rid of the Taliban's heavy-handed rule. Haji Wali Jan, a local MP, says the militants were taking money and food from people to “defend” them from the infidel government. But previous operations in Helmand have shown that clearing, bloody as it sometimes gets, is the easy part. Insurgents who melt away at the first push, tend to slip back to mount a bombing campaign later. This winter has already been bloodier for NATO than any since the war began, although that is partly the result of recent troop increases. An incompetent and corrupt Afghan administration, a mostly hopeless police force, and little economic development have so far ensured that any gains in security remain tenuous at best.